Story of Yudhishthira and the Yaksha’s Questions

A story of their forest life, I shall tell you here. One day the brothers became thirsty in the forest. Yudhishthira bade his brother, Nakula, go and fetch water.

He quickly proceeded towards the place where there was water and soon came to a crystal lake, and was about to drink of it, when he heard a voice utter these words: “Stop, O child. First answer my questions and then drink of this water.”

But Nakula, who was exceedingly thirsty, disregarded these words, drank of the water, and having drunk of it, dropped down dead. As Nakula did not return, King Yudhishthira told Sahadeva to seek his brother and bring back water with him.

So Sahadeva proceeded to the lake and beheld his brother lying dead. Afflicted at the death of his brother and suffering severely from thirst, he went towards the water, when the same words were heard by him: “O child, first answer my questions and then drink of the water.” He also disregarded these words, and having satisfied his thirst, dropped down dead.

Subsequently, Arjuna and Bhima were sent, one after the other, on a similar quest; but neither returned, having drunk of the lake and dropped down dead.

(Courtesy: Mahabharata by Gita Press)

Then Yudhishthira rose up to go in search of his brothers. At length, he came to the beautiful lake and saw his brothers lying dead. His heart was full of grief at the sight, and he began to lament.

Suddenly he heard the same voice saying, “Do not, O child, act rashly. I am a Yaksha living as a crane on tiny fish. It is by me that thy younger brothers have been brought under the sway of the Lord of departed spirits. If thou, O Prince, answer not the questions put by me even thou shalt number the fifth corpse. Having answered my questions first, do thou, O Kunti’s son, drink and carry away as much as thou requirest.”

Yudhishthira replied, “I shall answer thy questions according to my intelligence. Do thou ask me.” The Yaksha then asked him several questions, all of which Yudhishthira answered satisfactorily. One of the questions asked was: “What is the most wonderful fact in this world?” “We see our fellow-beings every moment falling off around us; but those that are left behind think that they will never die. This is the most curious fact: in face of death, none believes that he will die!”

Another question asked was: “What is the path of knowing the secret of religion?” And Yudhishthira answered, “By argument nothing can be settled; doctrines there are many; various are the scriptures, one part contradicting the other. There are not two sages who do not differ in their opinions. The secret of religion is buried deep, as it were, in dark caves. So the path to be followed is that which the great ones have trodden.”

Then the Yaksha said, “I am pleased. I am Dharma, the God of Justice in the form of the crane. I came to test you. Now, your brothers, see, not one of them is dead. It is all my magic. Since abstention from injury is regarded by thee as higher than both profit and pleasure, therefore, let all thy brothers live, O Bull of the Bharata race.”

And at these words of the Yaksha, the Pandavas rose up.

Here is a glimpse of the nature of King Yudhishthira. We find by his answers that he was more of a philosopher, more of a Yogi, than a king.

Now, as the thirteenth year of the exile was drawing nigh, the Yaksha bade them go to Virata’s kingdom and live there in such disguises as they would think best.

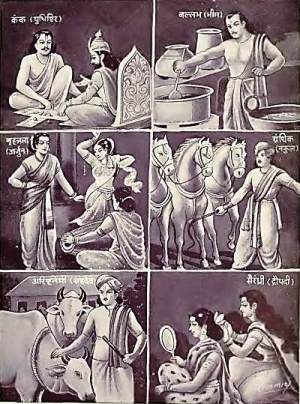

Pandavas Spend the 13th Year of Exile Living in Disguise in King Virata’s Kingdom

Yudhishthira disguised as a courtier, Bhima as a cook; Arjuna as a dance teacher; Nakula as the keeper of horses; Sahadeva in the cowshed and Draupadi as a waiting-woman.

(Courtesy: Mahabharata by Gita Press)

So, after the term of the twelve years’ exile had expired, they went to the kingdom of Virata in different disguises to spend the remaining one year in concealment, and entered into menial service in the king’s household.

Thus Yudhishthira became a Brahmana courtier of the king, as one skilled in dice; Bhima was appointed a cook; Arjuna, dressed as a eunuch, was made a teacher of dancing and music to Uttara, the princess, and remained in the inner apartments of the king; Nakula became the keeper of the king’s horses; and Sahadeva got the charge of the cows; and Draupadi, disguised as a waiting-woman, was also admitted into the queen’s household.

Thus concealing their identity the Pandava brothers safely spent a year, and the search of Duryodhana to find them out was of no avail. They were only discovered just when the year was out.

Then Yudhishthira sent an ambassador to Dhritarashtra and demanded that half of the kingdom should, as their share, be restored to them. But Duryodhana hated his cousins and would not consent to their legitimate demands. They were even willing to accept a single province, nay, even five villages. But the headstrong Duryodhana declared that he would not yield without fight even as much land as a needle’s point would hold.

Dhritarashtra pleaded again and again for peace, but all in vain. Krishna also went and tried to avert the impending war and death of kinsmen, so did the wise elders of the royal court; but all negotiations for a peaceful partition of the kingdom were futile. So, at last, preparations were made on both sides for war, and all the warlike nations took part in it.

Mahabharata War Begins

The old Indian customs of the Kshatriyas were observed in it. Duryodhana took one side, Yudhishthira the other. From Yudhishthira messengers were at once sent to all the surrounding kings, entreating their alliance, since honourable men would grant the request that first reached them. So, warriors from all parts assembled to espouse the cause of either the Pandavas or the Kurus according to the precedence of their requests; and thus one brother joined this side, and the other that side, the father on one side, and the son on the other.

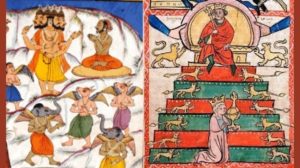

(Courtesy: Mahabharata by Gita Press)

The most curious thing was the code of war of those days; as soon as the battle for the day ceased and evening came, the opposing parties were good friends, even going to each other’s tents; however, when the morning came, again they proceeded to fight each other. That was the strange trait that the Hindus carried down to the time of the Mohammedan invasion.

Then again, a man on horseback must not strike one on foot; must not poison the weapon; must not vanquish the enemy in any unequal fight, or by dishonesty; and must never take undue advantage of another, and so on. If any deviated from these rules he would be covered with dishonour and shunned. The Kshatriyas were trained in that way.

And when the foreign invasion came from Central Asia, the Hindus treated the invaders in the selfsame way. They defeated them several times, and on as many occasions sent them back to their homes with presents etc. The code laid down was that they must not usurp anybody’s country; and when a man was beaten, he must be sent back to his country with due regard to his position. The Mohammedan conquerors treated the Hindu kings differently, and when they got them once, they destroyed them without remorse.

Mind you, in those days — in the times of our story, the poem says — the science of arms was not the mere use of bows and arrows at all; it was magic archery in which the use of Mantras, concentration, etc., played a prominent part. One man could fight millions of men and burn them at will. He could send one arrow, and it would rain thousands of arrows and thunder; he could make anything burn, and so on — it was all divine magic.

One fact is most curious in both these poems — the Ramayana and the Mahabharata — along with these magic arrows and all these things going on, you see the cannon already in use. The cannon is an old, old thing, used by the Chinese and the Hindus. Upon the walls of the cities were hundreds of curious weapons made of hollow iron tubes, which filled with powder and ball would kill hundreds of men. The people believed that the Chinese, by magic, put the devil inside a hollow iron tube, and when they applied a little fire to a hole, the devil came out with a terrific noise and killed many people.

So in those old days, they used to fight with magic arrows. One man would be able to fight millions of others. They had their military arrangements and tactics: there were the foot soldiers, termed the Pada; then the cavalry, Turaga; and two other divisions which the moderns have lost and given up — there was the elephant corps — hundreds and hundreds of elephants, with men on their backs, formed into regiments and protected with huge sheets of iron mail; and these elephants would bear down upon a mass of the enemy — then, there were the chariots, of course (you have all seen pictures of those old chariots, they were used in every country). These were the four divisions of the army in those old days.

Role of Lord Krishna in the Mahabharata War

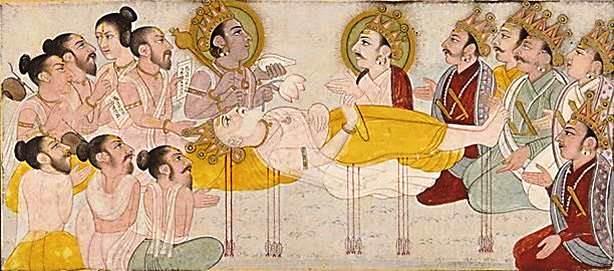

Now, both parties alike wished to secure the alliance of Krishna. But he declined to take an active part and fight in this war, but offered himself as charioteer to Arjuna, and as the friend and counsellor of the Pandavas while to Duryodhana he gave his army of mighty soldiers.

(Courtesy: Mahabharata by Gita Press)

Then was fought on the vast plain of Kurukshetra the great battle in which Bhishma, Drona, Karna, and the brothers of Duryodhana with the kinsmen on both sides and thousands of other heroes fell. The war lasted eighteen days.

Indeed, out of the eighteen Akshauhinis of soldiers very few men were left. The death of Duryodhana ended the war in favour of the Pandavas. It was followed by the lament of Gandhari, the queen and the widowed women, and the funerals of the deceased warriors.

The greatest incident of the war was the marvellous and immortal poem of the Gita, the Song Celestial.

It is the popular scripture of India and the loftiest of all teachings. It consists of a dialogue held by Arjuna with Krishna, just before the commencement of the fight on the battle-field of Kurukshetra.

I would advise those of you who have not read that book to read it. If you only knew how much it has influenced your own country even! If you want to know the source of Emerson’s inspiration, it is this book, the Gita. He went to see Carlyle, and Carlyle made him a present of the Gita; and that little book is responsible for the Concord Movement. All the broad movements in America, in one way or other, are indebted to the Concord party.

(Print of Lord Krishna by Raja Ravi Varma Press, conserved at the British Museum)

The central figure of the Gita is Krishna. As you worship Jesus of Nazareth as God come down as man so the Hindus worship many Incarnations of God. They believe in not one or two only, but in many, who have come down from time to time, according to the needs of the world, for the preservation of Dharma and destruction of wickedness. Each sect has one, and Krishna is one of them.

Krishna, perhaps, has a larger number of followers in India than any other Incarnation of God. His followers hold that he was the most perfect of those Incarnations. Why? “Because,” they say, “look at Buddha and other Incarnations: they were only monks, and they had no sympathy for married people. How could they have?

But look at Krishna: he was great as a son, as a king, as a father, and all through his life he practiced the marvellous teachings which he preached.” “He who in the midst of the greatest activity finds the sweetest peace, and in the midst of the greatest calmness is most active, he has known the secret of life.”

Krishna shows the way how to do this — by being non-attached: do everything but do not get identified with anything. You are the soul, the pure, the free, all the time; you are the Witness. Our misery comes, not from work, but by our getting attached to something.

Take for instance, money: money is a great thing to have, earn it, says Krishna; struggle hard to get money, but don’t get attached to it. So with children, with wife, husband, relatives, fame, everything; you have no need to shun them, only don’t get attached. There is only one attachment and that belongs to the Lord, and to none other. Work for them, love them, do good to them, sacrifice a hundred lives, if need be, for them, but never be attached. His own life was the exact exemplification of that.

Remember that the book which delineates the life of Krishna is several thousand years old, and some parts of his life are very similar to those of Jesus of Nazareth. Krishna was of royal birth; there was a tyrant king, called Kamsa, and there was a prophecy that one would be born of such and such a family, who would be king. So Kamsa ordered all the male children to be massacred.

The father and mother of Krishna were cast by King Kamsa into prison, where the child was born. A light suddenly shone in the prison and the child spoke saying, “I am the Light of the world, born for the good of the world.” You find Krishna again symbolically represented with cows — “The Great Cowherd,” as he is called. Sages affirmed that God Himself was born, and they went to pay him homage. In other parts of the story, the similarity between the two does not continue.

Shri Krishna conquered this tyrant Kamsa, but he never thought of accepting or occupying the throne himself. He had nothing to do with that. He had done his duty and there it ended.

Death of Bhishma

(Courtesy: Wikipedia)

After the conclusion of the Kurukshetra War, the great warrior and venerable grandsire, Bhishma, who fought ten days out of the eighteen days’ battle, still lay on his deathbed and gave instructions to Yudhishthira on various subjects, such as the duties of the king, the duties of the four castes, the four stages of life, the laws of marriage, the bestowing of gifts, etc., basing them on the teachings of the ancient sages. He explained Sankhya philosophy and Yoga philosophy and narrated numerous tales and traditions about saints and gods and kings. These teachings occupy nearly one-fourth of the entire work and form an invaluable storehouse of Hindu laws and moral codes.

After the Mahabharata War

Yudhishthira had in the meantime been crowned king. But the awful bloodshed and extinction of superiors and relatives weighed heavily on his mind; and then, under the advice of Vyasa, he performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice.

(Courtesy: Mahabharata by Gita Press)

After the war, for fifteen years Dhritarashtra dwelt in peace and honour, obeyed by Yudhishthira and his brothers. Then the aged monarch leaving Yudhishthira on the throne, retired to the forest with his devoted wife and Kunti, the mother of the Pandava brothers, to pass his last days in asceticism.

Thirty-six years had now passed since Yudhishthira regained his empire. Then came to him the news that Krishna had left his mortal body. Krishna, the sage, his friend, his prophet, his counsellor, had departed. Arjuna hastened to Dwaraka and came back only to confirm the sad news that Krishna and the Yadavas were all dead.

Then the king and the other brothers, overcome with sorrow, declared that the time for them to go, too, had arrived. So they cast off the burden of royalty, placed Parikshit, the grandson of Arjuna, on the throne, and retired to the Himalayas, on the Great Journey, the Mahaprasthana. This was a peculiar form of Sannyasa. It was a custom for old kings to become Sannyasins. In ancient India, when men became very old, they would give up everything. So did the kings. When a man did not want to live any more, then he went towards the Himalayas, without eating or drinking and walked on and on till the body failed. All the time thinking of God, he just marched on till the body gave way.

Then came the gods, the sages, and they told King Yudhishthira that he should go and reach heaven. To go to heaven one has to cross the highest peaks of the Himalayas. Beyond the Himalayas is Mount Meru. On the top of Mount Meru is heaven. None ever went there in this body. There the gods reside. And Yudhishthira was called upon by the gods to go there.

So the five brothers and their wife clad themselves in robes of bark and set out on their journey. On the way, they were followed by a dog. On and on they went, and they turned their weary feet northward to where the Himalayas lifts his lofty peaks, and they saw the mighty Mount Meru in front of them. Silently they walked on in the snow, until suddenly the queen fell, to rise no more.

To Yudhishthira who was leading the way, Bhima, one of the brothers, said, “Behold, O King, the queen has fallen.” The king shed tears, but he did not look back. “We are going to meet Krishna,” he says. “No time to look back. March on.” After a while, again Bhima said, “Behold, our brother, Sahadeva has fallen.” The king shed tears; but paused not. “March on,” he cried.

One after the other, in the cold and snow, all the four brothers dropped down, but unshaken, though alone, the king advanced onward. Looking behind, he saw the faithful dog was still following him. And so the king and the dog went on, through snow and ice, over hill and dale, climbing higher and higher, till they reached Mount Meru; and there they began to hear the chimes of heaven, and celestial flowers were showered upon the virtuous king by the gods.

Yudhishthira Refuses to Enter Heaven Without the Faithful Dog

Then descended the chariot of the gods, and Indra prayed him, “Ascend in this chariot, greatest of mortals: thou that alone art given to enter heaven without changing the mortal body.” But no, that Yudhishthira would not do without his devoted brothers and his queen; then Indra explained to him that the brothers had already gone thither before him.

(Courtesy: Mahabharata by Gita Press)

And Yudhishthira looked around and said to his dog, “Get into the chariot, child.” The god stood aghast. “What! The dog?” he cried. “Do thou cast off this dog! The dog goeth not to heaven! Great King, what dost thou mean? Art thou mad? Thou, the most virtuous of the human race, thou only canst go to heaven in thy body.”

“But he has been my devoted companion through snow and ice. When all my brothers were dead, my queen dead, he alone never left me. How can I leave him now?” “There is no place in heaven for men with dogs. He has to be left behind. There is nothing unrighteous in this.” “I do not go to heaven,” replied the king, “without the dog. I shall never give up such a one who has taken refuge with me, until my own life is at an end. I shall never swerve from righteousness, nay, not even for the joys of heaven or the urging of a god.”

“Then,” said Indra, “on one condition the dog goes to heaven. You have been the most virtuous of mortals and he has been a dog, killing and eating animals; he is sinful, hunting and taking other lives. You can exchange heaven with him. “Agreed,” says the king. “Let the dog go to heaven.”

At once, the scene changed. Hearing these noble words of Yudhishthira, the dog revealed himself as Dharma; the dog was no other than Yama, the Lord of Death and Justice. And Dharma exclaimed, “Behold, O King, no man was ever so unselfish as thou, willing to exchange heaven with a little dog, and for his sake disclaiming all his virtues and ready to go to hell even for him. Thou art well born, O King of kings. Thou hast compassion for all creatures, O Bharata, of which this is a bright example. Hence, regions of undying felicity are thine! Thou hast won them, O King, and thine is a celestial and high goal.”

Then Yudhishthira, with Indra, Dharma, and other gods, proceeds to heaven in a celestial car. He undergoes some trials, bathes in the celestial Ganga, and assumes a celestial body. He meets his brothers who are now immortals, and all at last is bliss.

Thus ends the story of the Mahabharata, setting forth in a sublime poem the triumph of virtue and defeat of vice.

In speaking of the Mahabharata to you, it is simply impossible for me to present the unending array of the grand and majestic characters of the mighty heroes depicted by the genius and master-mind of Vyasa.

The internal conflicts between righteousness and filial affection in the mind of the god-fearing, yet feeble, old, blind King Dhritarashtra; the majestic character of the grandsire Bhishma; the noble and virtuous nature of the royal Yudhishthira, and of the other four brothers, as mighty in valour as in devotion and loyalty; the peerless character of Krishna, unsurpassed in human wisdom; and not less brilliant, the characters of the women — the stately queen Gandhari, the loving mother Kunti, the ever-devoted and all-suffering Draupadi — these and hundreds of other characters of this Epic and those of the Ramayana have been the cherished heritage of the whole Hindu world for the last several thousands of years and form the basis of their thoughts and of their moral and ethical ideas.

In fact, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata are the two encyclopedias of the ancient Aryan life and wisdom, portraying an ideal civilization which humanity has yet to aspire after.

Please Note: Section headers have been added to this talk by Swami Vivekananda so as to allow for easy readability. They are not present in his original lecture.

- Other Posts I Recommend Reading

- VIDEO: Mahabharata & Karma | Some Stories Imply Karma “IS” Eye for Eye? Can You Explain?: This video debunks the Gandhari & Insect Eggs folklore related to the Mahabharata, which implies the law of karma is an eye-for-eye type of barbarism.

- Ramayana Summary | A Concise Retelling by Swami Vivekananda: An engaging retelling of the Ramayana by Swami Vivekananda. This Ramayana summary has been enhanced with beautiful paintings from the 17th century.

- Speaking Truth to Power | Vibhishan Risks His Life To Stand Up To Ravana: Story from the Ramayana illustrating Vibhishan’s courage to stand up to Ravana’s deplorable abduction of Sita & make him listen to the voice of truth.

- Prudence | Dasaratha’s Rashness and Death of Shravankumar: Mother Mirra explains the spiritual quality of prudence (thinking of the consequences before acting) using a tale from the Ramayana

- When a Sincere Person Like Rama Spoke His Words Destroyed Falsehood & Hypocrisy: Mother Mirra relates a story from the Ramayana that explains why a sincere person is able to destroy propaganda & expose the truth.